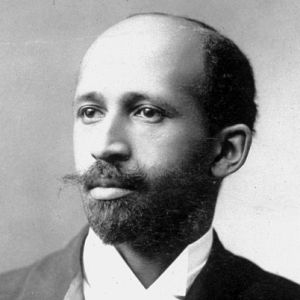

Fifty-two years ago today, on the day before The March on Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois died. Born in Great Barrington, Mass. just after the end of the Civil War, he had been a champion of civil rights and the pursuit of equality, a tireless advocate for African-Americans, and a writer of extraordinary power. A prodigious intellectual with a devotion to education, Du Bois had bachelor degrees from Fisk and Harvard, a Ph.D. from Harvard (the first black person to receive one there), with more advanced work in Berlin. He was a classics professor and a historian who wrote sociology, poetry, plays and fiction — to name just some of the fields in which he worked.

I wrote about Du Bois in Beyond the University: Why Liberal Education Matters. He championed liberal learning, seeing it as a vehicle for the development of humanity. As he said:

The function of the university is not simply to teach bread-winning, or to furnish teachers for the public schools, or to be a center of polite society; it is, above all, to be the organ of that fine adjustment between real life and the growing knowledge of life, an adjustment which forms the secret of civilization.

Du Bois believed that educational institutions should aim to stimulate hunger for knowledge — not just contain it or channel it into a narrow path destined for a job market that will quickly change. Education should not teach the person to conform to a function, a repetition of slavery, but should provide people with a wider horizon of choices.

Du Bois repeatedly defended liberal education against those who saw it as impractical. In an address at the Hampton Institute in the beginning of the century, he lamented that “there is an insistence on the practical in a manner and tone that would make Socrates an idiot and Jesus Christ a crank.” At one of the centers of industrial learning for blacks, Du Bois argued that its doctrine of education was fundamentally false because it was so seriously limited. What mattered in education was not so much the curriculum on campus but an understanding that the aim of education went far beyond the university. And here is where Du Bois issued his challenge:

The aim of the higher training of the college is the development of power, the training of a self whose balanced assertion will mean as much as possible for the great ends of civilization. The aim of technical training on the other hand is to enable the student to master the present methods of earning a living in some particular way . . . We must give our youth a training designed above all to make them men of power, of thought, of trained and cultivated taste; men who know whither civilization is tending and what it means.

Du Bois believed that a pragmatic liberal education made one more human, to be sure, but it also gave one an awesome responsibility. Education, as he consistently stressed, was a mode of empowerment, and those who benefited from it should help empower others. When liberal learning worked, students became teachers, creating a virtuous circle of education.

As we prepare to begin the academic year, let’s remember Du Bois’s challenge — and his hope!