Like many young Americans, I was introduced to Elie Wiesel in middle school by reading his harrowing Night. The deep darkness of the death camps, the permanent pain in survival, was seared into my consciousness. More than a decade later, I read his Hasidic Tales while living in Paris as a graduate student. I especially remember this story:

When the great Rabbi Israel Baal Shem-Tov saw misfortune threatening the Jews it was his custom to go into a certain part of the forest to meditate. There he would light a fire, say a special prayer, and the miracle would be accomplished and misfortune averted.

Later, when his disciple, the celebrated Magid of Mezritch, had occasion, for the same reason, to intercede with heaven, he would go to the same place in the forest and say: “Master of the Universe, listen! I do not know how to light the fire, but I am still able to say the prayers.” And again the miracle would be accomplished.

Still later, Rabbi Moshe-Leib of Sasov, in order to save his people once more, would go into the forest and say: “I do not know how to light the fire, I do not know the prayer, but I know the place and this must be sufficient.” It was sufficient, and the miracle was accomplished

Then it fell to Rabbi Israel of Rizhyn to overcome misfortune. Sitting in his armchair, his head in his hands, he spoke to God: “I am unable to light the fire and I do not know the prayer; I cannot even find the place in the forest. All I can do is to tell the story, and that must be sufficient.” And it was sufficient.

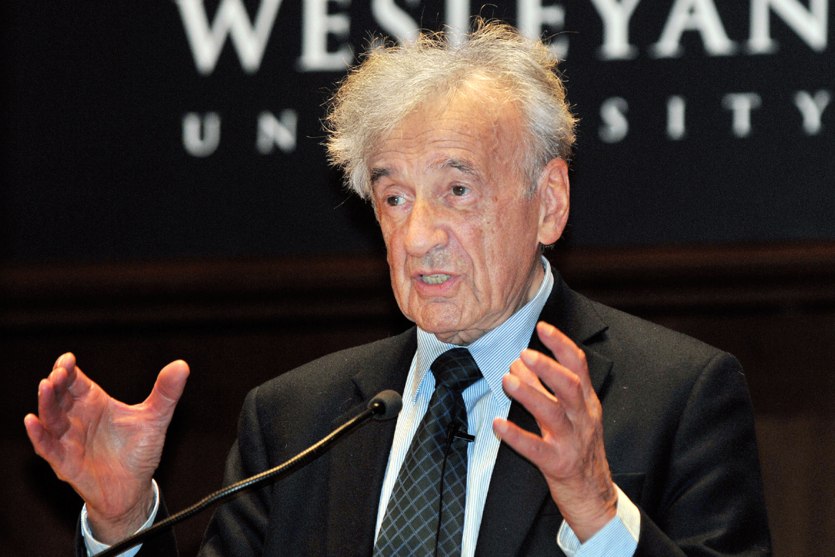

I met Elie Wiesel as a young professor in Claremont, California, and then had the pleasure of hosting a talk he gave at Wesleyan about six years ago. At dinner that night, our daughter Sophie asked him why he and other Jews didn’t flee from Nazi persecution. I was surprised (and maybe a little embarrassed) by her boldness. How many times must he have been asked this kind of question! Patiently, kindly, he told her “we had no idea, we could not even imagine what was to come.” I then told him that Sophie was to be bat mitzvahed later that spring. Taking her punim in his hands, he kissed her on the forehead as her eyes filled with tears. Mazel tov, mazel tov, he said.

That night, at his lecture Elie Wiesel told his story—as he did countless times over more than 60 years. He made every place he spoke that special place in the forest; he made every speech a kind of fire, maybe even a kind of prayer. I don’t know if his telling the story is sufficient, but I am so grateful to have heard him. May his memory be for a blessing.