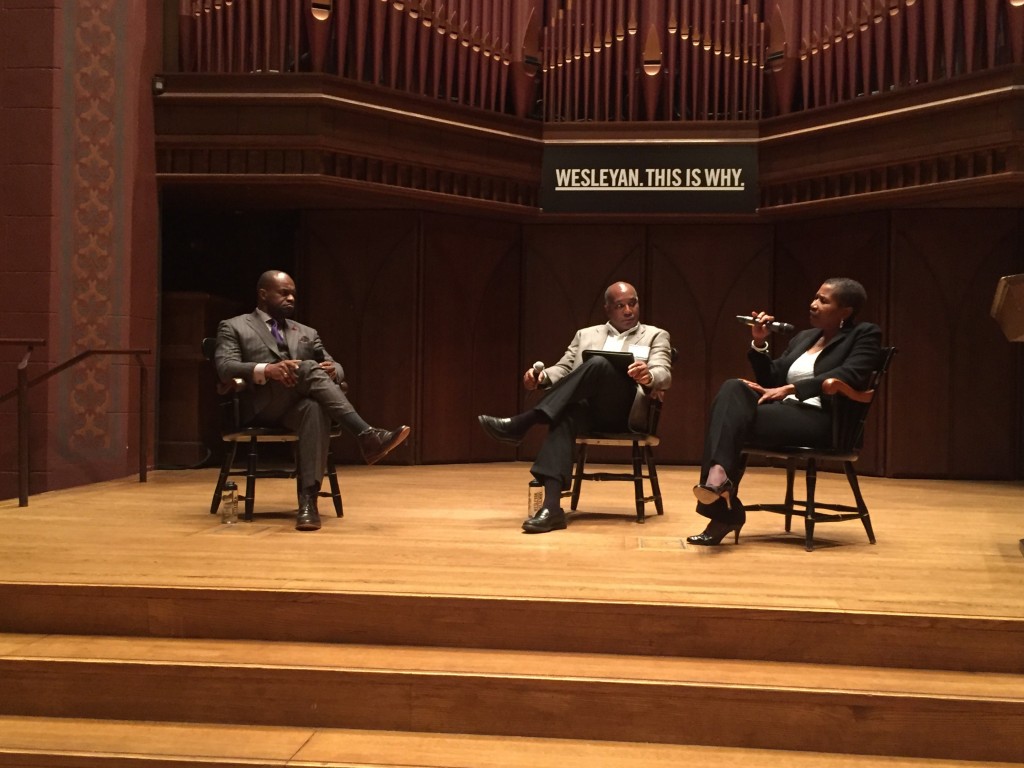

I recently reviewed Stanley Fish’s collection of columns from the New York Times. I have read his work with interest and pleasure for many years, and he takes on topics (free speech, BDS movement, pragmatism, academic freedom) that I find tremendously engaging. Prof. Fish will be delivering the Hugo Black lecture at Wesleyan on February 18th. My review appeared in The Chronicle for Higher Education last week.

Unprincipled on Principle

When The New York Times enlisted Stanley Fish as a columnist, it found a great partner in this literary critic — someone who writes with clarity about academic matters but who is at ease with everyday rhetoric. An accomplished Miltonist, professor of law, and university administrator, Fish has an uncanny feel for the interests and tastes of that obscure object of intellectuals’ desire: “generally educated readers.”

Princeton University Press has collected more than 90 of his Times columns in Think Again: Contrarian Reflections on Life, Culture, Politics, Religion, Law, and Education. The productive Fish is not served well by either the quantity or the selection. Each piece is short, so it seems churlish to complain about any one of them, or even about the redundancies in the points made and the enemies skewered. But we can Google Professor Fish’s favorite movies and his country-music choices — we don’t need them collected in a book. And how many times does one have to resurrect the New Atheists and academic activists just to bury them again with argument and scorn?

These are minor quibbles with a volume that covers so much ground so thoughtfully. Whether he is writing about French theory, religion, poetry, law, liberal education, or politics in upstate New York — where he tries hard to be just an ordinary guy (in his country home) — Fish is both stimulating and precise. He doesn’t strive for consistency, but he manages to achieve the coherence of a pragmatist. His ideas hang together so they can be put to work.

But they don’t hang together around any principle, save one that denies the point of having one. “Knowledge is irremediably perspectival,” he writes in the introduction, “and perspectives are irremediably political.” This is the kind of thing that lots of people have said over the past 50 years, many of whom thought they were being progressive or radical. Fish joined in the merry iconoclasm in the early stages of his career, but now he prefers a more curmudgeonly posture.

In Fish’s world there are no solid foundations — that’s part of what it means to say that knowledge is perspectival. From my perspective, your solid foundation looks pretty shaky — just an accumulation of privilege acquired through oppression, ripe for critique. My critique, of course, is based on another “privilege,” on another accumulation of shared language and beliefs. When people defend their positions, they are really just appealing to their preferred group — those who share their perspective and perhaps their privilege (or their critique of privilege).

In the heady days of deconstruction and postmodernism, Fish’s arguments were taken to be part of the wave of anti-establishment thinking. Not so, he retorted: You can develop better defenses of the establishment without foundations. Fish has made this pragmatist point again and again: When you take away foundations and goals, you really aren’t taking away anything important. The loss of the goal of absolute knowledge doesn’t keep us from “do[ing] all the things we have always done; we can still say that some things are true and others false, and believe it.” We always made these statements in relation to our group’s perspective; now we can just give up the ultimate justification talk. “The world, and you,” he writes, “will go on pretty much in the same old way.”

This is an argument tailor-made for annoying nearly everyone. Conservative scholars who believe in ultimate grounds for truth and morality find Fish’s anti-foundationalism anathema. The alternative to Truth with a capital “T,” they want to believe, is relativism, chaos, nihilism. On the other hand, scholars who believe they have destroyed something essential when they have deconstructed metaphysics and religion are similarly disappointed. When someone claims to have shown that a belief system or social practice is socially constructed, they haven’t, in fact, generated any particular political position at all. “Believing or disbelieving in moral absolutes is a philosophical position, not a recipe for living.”

A philosophical position is merely academic for Fish, separate from any kind of recipe for living. Professors, he has reminded his readers, should “just do their jobs” — which means introducing students to bodies of material and helping them develop analytical skills. He is impatient with the rhetoric of character building, citizenship, or leadership. The humanities are at the core of a liberal education, Fish declares, but their only justification is “the pleasure they give to those who enjoy them.”

As a pragmatist, Fish should know that justification always depends on the audience one is addressing. But he oddly seems to believe that literature needs to be kept unsullied by arguments that might appeal to nonacademics. Fish keeps repeating his narrow version of the “job description” of professors but has no arguments for the purity of academic purpose; he must know there is no real basis for his dictum “always academicize.” Does he really think that the humanities will get more support on the basis of aesthetic wonderment rather than civic engagement? He’s too smart for that. Fish abandons a pragmatic attitude because he just enjoys (more than is necessary) popping the puffery of activist professors who confuse opinions formed while reading blogs and magazines with knowledge developed through research and analysis.

Fish appears to have one thing in common with the radical scholars he critiques, and that’s contempt for liberalism. For the radical, liberals are too invested in the status quo, and their supposed neutrality only perpetuates injustice. For Fish, liberals evince a wrongheaded commitment to pure procedure and abstract principle. They can’t take religion (or any strong content) seriously because they retreat to ideals of fairness and process. Fish knows that “fairness” and “process” are always determined by one’s own group — there is no meta-procedure that escapes all contexts to render a perfectly fair judgment.

He is right about the impossibility of pure procedure, but many contemporary liberals would agree with him. The fact that you can’t have a view from nowhere doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to see an issue from another person’s point of view. To do so, even Fish admits, is just “serious thought.” But Fish’s fear of being a mere liberal drives him to fetishize academic purity and aspire to a higher neutrality. “I don’t stand anywhere,” he writes; “that’s the (non)point of most of these columns.”

Of course, Fish stands somewhere; he just doesn’t want to be caught doing so. Too bad. In these provocative, intelligent essays, Fish winds up taking stands to support his own “genuine pleasure,” and usually this is engaging enough. But he could have taken a page from another pragmatic anti-foundationalist, Richard Rorty. “The point of reading philosophy,” Rorty wrote, “is not to find a way of altering one’s inner state, but rather to find better ways of helping us overcome the past in order to create a better human future.” Now there’s a reason to “think again.”