Each year I send out an end of the year message to the Wesleyan community. I’ve pasted it below.

Dear friends,

In sharing some reflections on the year, I’ll begin with how it ended — with phrases from Commencement still ringing in my head. There’s the wish of Beverly Daniel Tatum ’75 for the class of 2015: “May you find for yourselves that place where your deep gladness meets the world’s deep need.” And Senior Class Speaker Marissa Castrigno’s description of the student community as “a stronghold of dialogue, of passion, of intelligence.” There’s praise from Daphne Kwok ’84 of Baldwin Medal winner Alan Dachs ’70 for his “unstinting commitment to the public good and to alma mater.” And, of course, the dramatic reprise by Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02 of a line from his Broadway show: “I’m not throwing away my shot.”

A record 799 graduating seniors enjoyed that beautiful day. Hardly the only record set this year. Our athletes set 32! Our baseball and men’s basketball teams were NESCAC champs, and tennis star Eudice Chong ’18 was National Division III champion! There is much to be proud of in other realms of course. In the best Wesleyan tradition our students challenged complacency and advocated for their beliefs all while pursuing their studies intensely. Often study and challenge overlapped, as with CSS major Isabella Banks ’15, awarded a prestigious Watson Fellowship for her exploration of alternatives to the criminal justice system.

Our Admission results this year were excellent, especially for first-generation and low-income students. Our “yield” was the highest in memory, and the class of 2019 will be the most international ever, with a record number of applicants having made Wes their first choice.

We’ve made huge progress in getting our financial house in order, building our capacity for the future. We continue to find ways to improve access. This year we once again raised tuition much less than did peer schools, and recently The Chronicle of Higher Education pointed to progress in one of our affordability initiatives, the three-year degree. Our cohort of military veterans finished their first year at Wesleyan, all on scholarship and all successful in their studies.

Of course, not all has been rosy throughout the year. As many of you will have read, too many of our students made poor choices in regard to drugs and alcohol — putting themselves and others at risk. We remain committed to making our campus safe, equitable, and inclusive. There is work to be done — by students as well as staff — and it will get done.

One of the many joys of Commencement for me is presenting the Binswanger Prizes for Excellence in Teaching: this year to Professors Calter, Schorr, and Ulysse. Wesleyan faculty take teaching seriously, and we expect the new Center for Pedagogical Innovation to be a nexus of collective teaching intelligence. Thanks to generous individual and foundation support, we are doing more with project-based learning and exploring innovative offerings in design and engineering. Wes faculty are not only great teachers, they’re impressive researchers too, and this year many of our professors won major grants and prizes. From book publications to exhibitions, performances and scientific articles, the Wes faculty help shape our culture.

New this spring was the Riverfront Festival, sponsored in part by the Center for the Arts, which attracted people from around Middlesex County. Improving connections with Middletown was one of many recommendations from our campus planning consultants (their report will be available in a week or so on the homepage). Of special interest, I think, were their suggestions for improving informal learning spaces. Interaction among students has always been one of the joys of the Wesleyan experience, and it’s time to take a look at how our current spaces enable or inhibit participation in campus learning.

Thanks to the inspiring generosity of our community, the THIS IS WHY fundraising effort has been far and away the most successful campaign in Wesleyan history. Over 70% of our alumni have already made a gift, and we have raised over $402 million with still another year to go! Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

With the gifts raised so far, 117 new scholarships have been endowed. That’s terrific, but it’s not enough. The newly admitted class has set another record, receiving more financial aid than any prior group! The need for financial aid will only grow. This is why we made endowing aid our #1 campaign priority, and this is what we are focused on in the last year of the campaign.

Our graduating seniors had much to celebrate, and so do we all who care for Wesleyan. Our collective giving — your giving — has made Wesleyan an institution where boldness, rigor, and practical idealism are apparent every day. It’s July 2015, which means the final year of our campaign has officially begun. The campaign will only be the success we want it to be if it finishes strong. I invite everyone to join in its success by making a gift during this last year.

• I’m not throwing away my shot

• Unstinting commitment to the public good and to alma mater

• A stronghold of dialogue, of passion, of intelligence

• May you find for yourselves that place where your deep gladness meets the world’s deep need

THIS IS WHY.

Sincerely,

Michael S. Roth

President

Early morning arrivals

Early morning arrivals

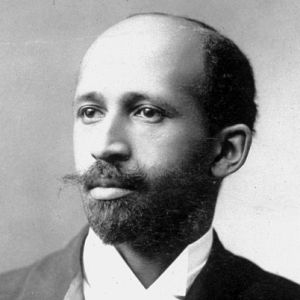

There were almost 5oo applications for the new program, and only 36 were successful. Of these, two are Wesleyan faculty!

There were almost 5oo applications for the new program, and only 36 were successful. Of these, two are Wesleyan faculty! Jennifer Tucker has taught in the history, FGSS, and SISP programs, and not long ago was running the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life. Jennifer has long been interested in the intersection of visual culture and science, and her project on the emergence of facial recognition system technology will have broad impact. Jennifer expects to write a wide-ranging account of how the project of capturing the defining features of an individual face has led to current modes of surveillance and law enforcement, digital privacy and individuality.

Jennifer Tucker has taught in the history, FGSS, and SISP programs, and not long ago was running the Allbritton Center for the Study of Public Life. Jennifer has long been interested in the intersection of visual culture and science, and her project on the emergence of facial recognition system technology will have broad impact. Jennifer expects to write a wide-ranging account of how the project of capturing the defining features of an individual face has led to current modes of surveillance and law enforcement, digital privacy and individuality.