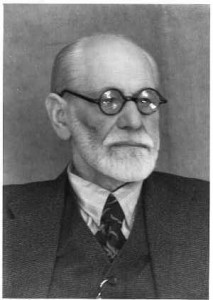

Sigmund Freud asked to offer a guest blog. We posted it yesterday on The HuffingtonPost.

In December I enjoyed announcing to the guards at The Jewish Museum that my name was Sigmund Freud, and that I was coming for the Wish You Were Here event. I died in 1939 (and it was enough already), but Michael Roth had been invited to speak for me, as me. Roth was interviewed in my place — not just to talk about me. He’s a historian, unanalyzed I regret to say, but he did curate a large exhibition about my work that came to the museum almost 20 years ago. How he had the chutzpah to speak as me I can’t say, but the crowd seemed to really enjoy it. He probably went too far in his nasty (but accurate) characterization of Jung, but hey, it’s a Jewish Museum.

When the museum agreed to accept the exhibition about my work in the 1990s, it was a brave act. Psychoanalysis is controversial, and at that time its detractors were making nice careers for themselves. When even the plans for the exhibition were under sharp attack, The Jewish Museum stepped forward and agreed to be a venue for the show, Freud: Conflict and Culture. This was an institution that would take risks, and so I wasn’t all that surprised in December when the head curator announced that Franz Kafka would be the next speaker in the series, and that the controversial feminist philosopher Judith Butler would speak for Kafka. I was proud to be in the museum at that moment, even in the guise of Michael Roth. After all, museums are not just custodians of culture, they should be places of active engagement. Roth tells me that Judith Butler had been wrestling with Kafka for years, and that she is among our most fertile philosophical minds. She is also a supporter of the BDS movement to isolate Israel and challenge its occupation of the territories. But she wasn’t asked to talk about Israel. She would be Kafka, and at a Jewish museum they would be able to live with that tension. Good.

But no. Roth tells me that the event has been cancelled because Butler’s politics are just too controversial. Here’s what the press release says:

While her political views were not a factor in her participation, the debates about her politics have become a distraction making it impossible to present the conversation about Kafka as intended. Butler offers this comment: “I was very much looking forward to the discussion of Kafka in The Jewish Museum, and to affirm the value of Kafka’s literary work in that setting.”The March 6th program “Wish You Were Here: Franz Kafka” will not take place.

What a sad commentary on the Jewish community’s tolerance for debate these days! It’s not as if the event had to be cancelled because of the philosopher’s views on Kafka made her an inappropriate spokesperson for the writer. The fact that Butler had taken a strong stand against a particular variety of Zionism just disqualified her from talking about one of the most important writers of the last century. Now, I’m no literary critic (my tastes run toward crime fiction and the fantastic these days), but Franz Kafka would seem like just the right person to “bring back” after having spoken with me about how to understand the disguises we use to mask our conflicting impulses. But apparently, even in the New York Jewish community, culture we can debate about, but conflict over Israel we cannot abide.

Roth tells me in America today conflict is everywhere, but that people are determined to hear only from those with whom they know they will agree. Around the time he was speaking for me in New York, he wrote an angry op-ed condemning the American Studies boycott of Israeli universities, calling it “a repugnant attack on academic freedom.” Roth has known Butler since they were both young assistant professors, and he strongly disagrees with her approach to Israel and the occupation. He just doesn’t understand why this kind of disagreement should get in the way of hearing her bring Kafka back for a conversation. So now he wants to collaborate on a short essay critical of a cultural context in which a gifted philosopher won’t be able to talk about European literature because of her views on Middle East politics. You’re reading it.

Having lived most of my life in Vienna, I know a little something about conflict. It’s easier (and sometimes even necessary) to find groups with which you agree and get reinforcement for your own views. But this is a dangerous business; you can lose your ability to learn from difference and conflict — the wellsprings of real cultural development. That’s why cultural boycotts are so debilitating — whether it’s the refusal to hear from Israeli professors or the refusal to hear from an anti-Zionist philosopher. Isolating yourself from voices with whom you might disagree is also a sign (need I say it?) of your own insecurity about the views you claim to hold so dearly. Fear of your own error is often expressed as aggression against an outsider’s view.

But another op-ed? I asked Roth whether he thought people only read essays with which they knew they’d agree. Only one way to find out, he replied.