Kari received the sad news recently that Franklin Reeve, emeritus professor in the College of Letters, had passed away. He had taught at Wesleyan for more than 40 years, and his students and colleagues recognized his generosity, his wit, and his wide-ranging intellect. I didn’t study with Frank, but many of my friends did, and I experienced him as a formidable presence on campus. No, that’s not quite right. He had stature, but he also had a ready smile and an easy openness to which so many of my peers responded. A few years ago, Frank came back to campus with a jazz combo for an evening of music and poetry. He still had that openness, along with his lifelong joy in the careful use of language and in the vitality of improvisation.

Paul Schwaber, Frank’s colleague for many years in the COL has written a tribute to his friend. It’s my pleasure to post it below.

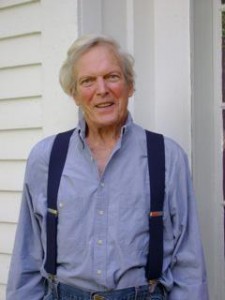

I remember Frank Reeve as a tall, extremely handsome man. He smiled ruefully and spoke very rapidly, as if barely able to control his rush of thought or questions. He joined COL after some time away from Wesleyan, where he’d initially taught Russian. Widely learned, he was polylingual, witty, keen with pun and irony. He wrote poetry, drama, fiction. He translated. He seemed never to stop writing. He was competitive and judgmental, but only with the best. To a young colleague he was also kind. For example, I asked him early on to read a review I’d not yet submitted on a new book by Robert Lowell. Frank made several helpful suggestions about phrasing but also telegraphed dubiety about my choice of poets. In COL’s jointly taught colloquia, he was energizing, a playful presence, exciting to teach with, inspiring by example to the students. I’ve known him to be sharply critical but never nasty, and he had no trouble communicating his love of language and linguistic art. Most of all he was both literary and worldly. There were few things he seemed not to know. COL applied for and won an NEH grant for courses on Science as a Humanistic Discipline, for which Frank taught a course called “How Things Work.”

He also noted when things didn’t work. My friend Bill Firshein and I volunteered to join Ted Hoey sail his new boat on the Connecticut River. Ted was a rookie, and Bill and I had never sailed. We learned that “Hard-a-lee” meant bend down quickly, as the main sail would swing by. Yet soon we three were in the water, the boat on its side, while we tried to roll it upright, laughing hard, as Bill, the biologist, shouted “Don’t swallow the water! It’s polluted!” Suddenly we were aware of a boat circling round us protectively. And there was Frank, with a boatload of wide-eyed children, he taller even than usual, with an amused—or was it pitying?—look on his face. He was an expert sailor, a committed teacher of literature and writing, with a lively and enlivening mind. He taught a seminar on Melville and Dostoevsky, two giants rarely studied in depth together. Yet it was much in demand, each time he offered it. For several years too he taught a first-year Great Books course, lecture size and ever-popular, in which apparently he was able to get the students to talk, and to talk with one another. It became a major source of gifted students to the COL major as well.

In his later years, he suffered crippling arthritis, which bent this exceptional man over but did not crush his spirit. We mourn his death and praise him, a genuine and unique man of letters.

It was an honor to be on the faculty with Frank Reeve, a great scholar and poetic translator who brought Robert Frost to Russia and Bella Akhmadulina to Wesleyan. He was always kind, witty, and inspiring. Rest in peace.

True to form, Frank was father to the movie Superman, Chris Reeve

Frank was my favorite professor. I was fortunate enough to take three course with him, the Melville and Dostoyevsky seminar mentioned above (I will never read that much in that short a period of time again), a creative writing class and a class on Poetries and Sciences. I could regale anyone who reads this with many wonderful stories about Frank but the first day of that Poetries and Sciences class was the most important. He asked us, “Where are we?” “In a classroom.” “So, physical space defines where you are?” “At Wesleyan.” “So, an occupation or organization defines where you are?” “In Middletown?” ” So, a city defines where you are?” Here we were, all these bright, young minds, all struggling to be the first one with the right answer. Frank just stared us down until we finally caught on that there was no right answer. Then, we could begin to figure out how poetry and science both help us to figure out the world. Without any right answers. Frank taught me how to think.

May his memory be a blessing to all those who were lucky enough to have known him.

I had Franklin Reeve as a professor in a freshman humanities class in the fall of 1962. He was quite young then, admirably impressive in looks and intellect, and a little scary to this middleclass boy from Iowa. I found the course very interesting, and I worked hard to absorb the reading assignments and write good papers, but I knew I wasn’t fully understanding what he was saying in class. I met with him during office hours and explained my difficulties. After a while he summarized, “It sounds like you’re saying I’m talking above your head, right?” I nodded. “RAISE YOUR HEAD!” he said, with a smile. I did. I started reading extra books about the material we were discussing, and also read books about effective writing. I eventually graduated as co-valedictorian of the class of ’66 and went on to have a successful academic career. I feel very fortunate to have had Professor Reeve as an inspiring teacher when I was 19 years old.

I loved and admired Frank. He was an artist, an inspirational teacher, and a great friend.

Those of us in the COL class of 2002 were very lucky to share a final year at wesleyan with him. That may we graduated and he retired.

I will never forget the time he brought a case of coronas to our last colloquium, or the speech he gave at our graduation after winning the excellence in teaching award. I had checked beforehand and told him that there would not be an opportunity to say anything, but he promised to give a speech anyway. And upon receiving his award he headed to the microphone and among other things, he wished for us that in life… should our bread fall, that it would land butter side up.

I had a writing tutorial with Franklin Reeve and he was honest and supportive. He kept in touch with me to tell me what he was writing after he retired and I always appreciated hearing from him. I am saddened by his death.

I loved and admired Frank as an artist, an inspirational teacher, and a great friend.

Those of us in the COL class of 2002 were very lucky to share our final year at wesleyan with him. That May we graduated and he retired.

I will never forget the time he brought a case of coronas to our last colloquium, or the speech he gave at our graduation after winning the excellence in teaching award. I had checked beforehand and told him that there would not be an opportunity to say anything, but he promised to give a speech anyway. And upon receiving his award he headed to the microphone and among other things, he wished for us that in life, should our toast fall, that it would land butter side up.

Franklin clearly accepted the tragedy of the human condition. He employed his great gifts, both socially and in his creative work, toward the end of making that burden more tolerable.

How could this be? The nicest of men, the most intelligent of academics, fatherly to his students, brilliant, witty, caring, fun–Rest in Peace.