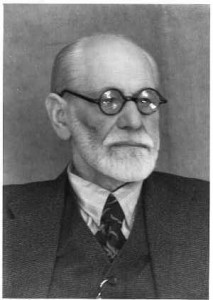

My review of Adam Phillips’ excellent new biography of Sigmund Freud, Becoming Freud: The Making of a Psychoanalyst, was published in the Washington Post today. I’ve been writing about Freud ever since my frosh classes at Wesleyan, and every so often I still return to psychoanalysis. In reading Phillips’ account of Freud’s early years, I was reminded of Hayden White’s remarks at this year’s Commencement.

“You can change your personal past. You do not have to continue to live with the past provided to you by all of the agencies and institutions claiming authority to decide who and what you are and what you must try to be in your future. You can change your past and thereby give your future a direction quite different from what has been marked out for you by others.” — Hayden White

White told our graduating class that “the future you deserve depends on the past you make for yourself.” Not bad advice…and very much related to the view of the self and of history that Freud developed in his early years

BECOMING FREUD

The Making of a Psychoanalyst

By Adam Phillips

The introduction to Adam Phillips’s new book is titled “Freud’s Impossible Life,” and the author makes clear more than once his view that the biographer’s task is an unmanageable one. Freud himself didn’t make things easy, destroying a lot of evidence of his early years so as to lead (as he said) his future biographers astray. And he did this long before he had anything like the kind of résumé that would have interested biographers.

As Phillips notes, Freud had a strong distrust of the biographer’s task, although he himself wrote speculative biographical studies. “Biographical truth is not to be had,” Freud wrote, “and if it were to be had we could not use it.” So much of a person’s life is underground, unconscious, and how we reconstruct it may reveal more about ourselves than about our subject. Phillips draws on two big Freud biographies (by Ernest Jones and Peter Gay), fully aware of their limitations.

In writing about Freud’s first 50 years, the author (who is also a practicing psychoanalyst) doesn’t have much evidence to go on. “Nothing, it is worth repeating, is properly known about Freud’s mother,” Phillips emphasizes, and he is also reduced to general speculations (or silence) about his father, wife, siblings and children.

But there is also freedom in the lack of evidence; one of the reasons Freud was so interested in the ancient world, Phillips tells us, was the paucity of verifiable facts. According to psychoanalysis, “only the censored past can be lived with,” and we “make histories so as not to perish of the truth.” For Phillips, psychoanalysis is part of the history of storytelling, and “a biography, like a symptom, fixes a person in a story about themselves.” What kind of story, then, does Phillips have to tell about Freud and about psychoanalysis?

His story about the life and the work is ultimately more invested in the latter. Young Freud, a secular Jew, tries to assimilate into Viennese society while also theorizing that we humans have desires that can never be assimilated with our public, social roles. He is attracted to mentors who introduce him to painstaking scientific research (Ernst Brücke), to charismatic investigations into the irrational (Jean-Martin Charcot), to clinical work that reduces hysterical misery to common unhappiness (Josef Breuer) and finally to unstable speculation on the secrets of human nature (Wilhelm Fliess). “In this formative period of his life,” Phillips writes, “Freud moves from wondering who to believe in, to wondering about the origins and the function of the individual’s predisposition to believe.”

As a young doctor in training at Vienna’s General Hospital, Freud asked his fiancee to embroider two maxims to hang in his lodgings: “Work without reasoning” and “When in doubt abstain.” This is so telling for Phillips because work and abstinence would eventually be at the center of psychoanalysis — both paradoxically reframed as dimensions of our circuitous pursuits of pleasure. The Freudian question par excellence: “What are you getting out of your abstinence?”

Phillips does tell us that, as a young child in the 1860s, Sigmund regularly found himself displaced by the birth of new siblings — six in seven years. As newlyweds in the 1880s, Freud and his wife practically repeated this history, welcoming new children — six in eight years. Surrounded by all these little ones, the young father spent more and more time trying to understand their demands on the world around them — how they communicated those demands and how adults responded.

One of the most important ways we deal with the demands we make and those made on us is to try to forget them. Unmet demands — unrequited desires — can hurt, and so in order to get back to work (and love), we may push them away. Frustration and the repression of frustration became central to Freud’s thinking in the 1890s, when he was in his late 30s and his 40s. At first he tried to understand the phenomena of pleasure, frustration and forgetting at the neurological level. Then he started paying attention to how we express in disguised form the complications of our appetites — in symptoms, in slips of the tongue, in jokes and especially in dreams: the beginning of psychoanalysis.

Now Sigmund could become a Freudian — an interpreter who showed how our actions and words indirectly express conflicts of desire. The conflicts among our desires never disappeared; they become the fuel of our histories. Making sense of these conflicts, understanding our desires, he thought, gives us an opportunity to make our histories our own.

Freud came to this realization, indeed, came to psychoanalysis, when he acknowledged that “our (shared) biological fate was always being culturally fashioned through redescription and recollection.” Our fate, then, resulted from how we remembered and retold our histories, and psychoanalysis became a vehicle for telling those histories in ways that acknowledged our conflicting desires. Psychoanalysis wasn’t a methodology to discover one’s true history; it was a collaboration that allowed one to refashion a past with which one could live.

In prose that often crackles with insights, Phillips refashions the heroic period in Freud’s life, when he believed “that making things conscious extended the individual’s realm of choice; where there was compulsion there might be decision, or newfound forms of freedom.” At the turn of the century, before there were many followers and before there was an organization to control, “Freud emerges as a visionary pragmatist.”

This visionary pragmatist understood that we could construct meaning and direction from our memories in order to suffer less and live more fully in the present. Phillips tells a story of how Freud came to that realization, making psychoanalysis as he made his life his own.