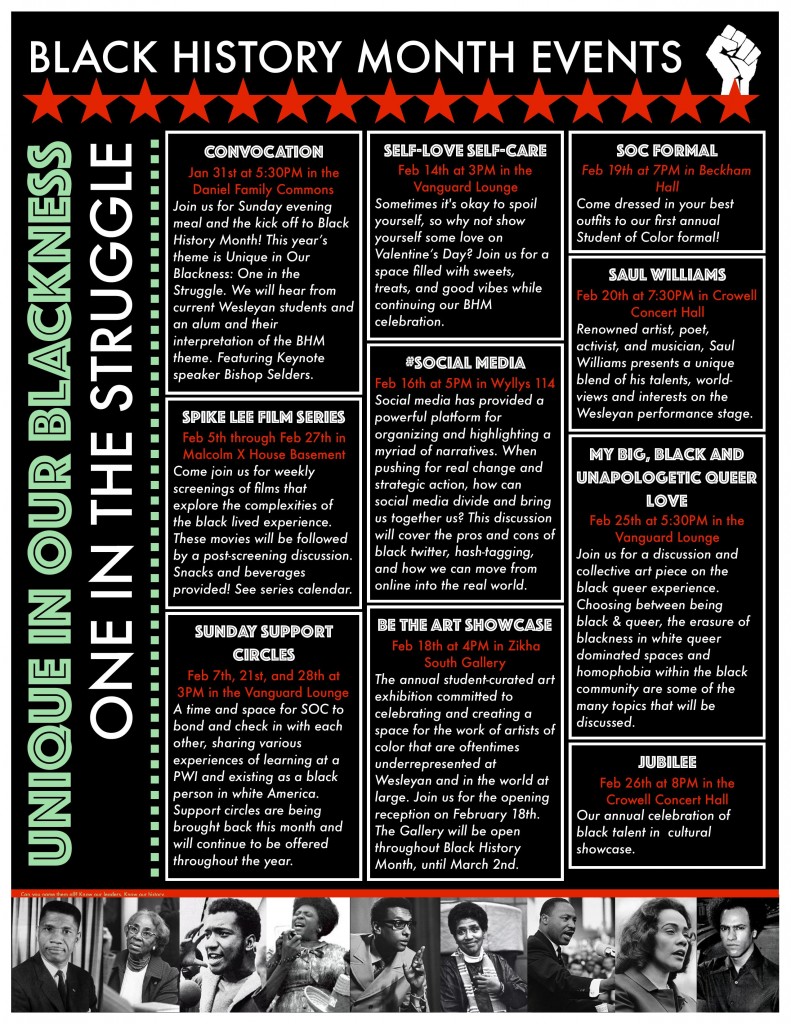

As we mark the midpoint of this cold month of February, it’s a good time to recall the resources on campus and elsewhere for Black History Month. Wesleyan began Black History Month with an engaged campus dialogue led by Dr. Dorceta Taylor that included students, faculty, staff, and Middletown community members. Over 400 members of our campus and surrounding community attended the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration and were encouraged to find practical ways to find common ground on environmental justice. I encourage us all to take an active part in supporting the work students of Ujamaa have done to underscore various dimensions of the African-American experience.

There are so many resources available today to explore African-American history. Here are just two: The New York Times is publishing a series of photographs and other documents that illuminate the historical experience of blacks in the U.S. You can find many in the “what’s going on in this series” pictures here. Digital Schomburg is an amazing compendium of sources on the global black experience. Exploring these sites, and attending various events on campus can help make Black History month more meaningful for everyone.