Colleges and universities love to celebrate successful alumni. The most compelling stories about the value of the undergraduate years are built on the connections between what one studies on campus and success beyond the university. At Wesleyan, we do whatever we can to shine a bright light on the achievements of our graduates—in the sciences and in the public sphere, in sports, in the business world and in academia. A few years ago we had a field day when In The Heights won Tony Awards and thrust its star, Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02, into the spotlight. He had originally produced the show on campus as a student, and then with director and Wesleyan alumnus Tommy Kail ’99, and playwright Quiara Alegria Hudes (now on the Wesleyan faculty), made a sparkling Broadway debut.

Even after the great success of Heights, nobody was really prepared for the truly revolutionary musical Hamilton. But given the liberal education that Miranda and Kail received at Wesleyan, maybe we should have seen something like this coming. Steeped in history and uncannily responsive to contemporary culture, it is an extraordinary artistic achievement at once traditional and experimental. That’s the kind of synthesis that those of us working in liberal arts colleges are always hoping for: making the past come alive in ways that expand possibilities in the present. Hamilton’s source is a deep historical biography by Ron Chernow, which Miranda somehow transformed into a hip-hop opera that draws on Broadway traditions to make something profoundly original.

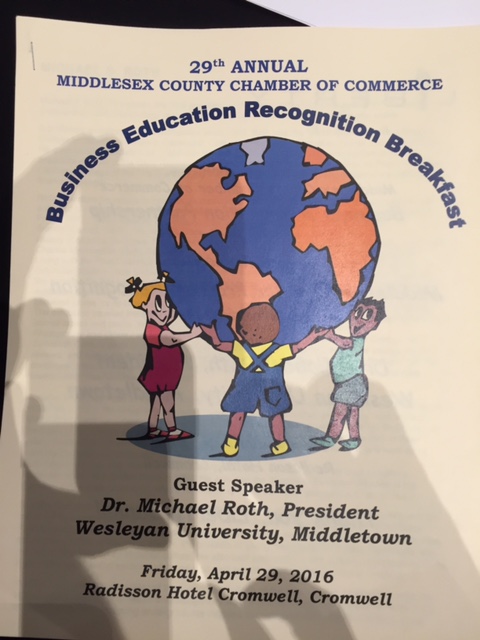

As we thought about the best way to honor this achievement, we decided to create a major prize to recognize creative potential in a student beginning her or his academic career at Wesleyan. This week we are announcing the Hamilton Prize: awarded to the incoming student (class of 2021) who has submitted (with the application for admission) a work of fiction, poetry, song, or creative nonfiction judged to best reflect originality, artistry and dynamism. The Hamilton Prize includes a full tuition scholarship at Wesleyan for four years. The winner of the prize will be selected by a panel of distinguished faculty and alumni.

Hamilton is a major event, and this is a major prize. Wesleyan has had a strong history of great writing. From poet laureate Richard Wilbur back in the days when I was a student to novelist Amy Bloom, biographer Lisa Cohen and playwright Quiara Alegria Hudes today, dynamic writers have made our campus their home. The tension between the traditional and experimental continues to energize students here—from the graphic novelist finding new audiences to the slam poet or songwriter wowing fellow students, bold writing is often combined with performance on campus. With the Hamilton Prize, we mean to signal our pride in a diverse array of creative endeavors.

When Hamilton’s generation considered higher education, many believed it was crucial that students not think they already knew at the beginning of their studies where they would end up when it was time for graduation. For all those who have followed on this American path of liberal education, learning was all about exploration – and you would only make important discoveries if you were open to unexpected possibilities. W.E.B. Du Bois was on that path when he argued a century later that a broad education was a form of empowerment that must be open to those disenfranchised by the economy or by legacies of discrimination. Lin-Manuel Miranda was also on that path when he created a musical of revolution that shows how the proverbial “dead white men” can be re-imagined for our time.

As some schools succumb to fears of being left behind and choose vocational shortcuts for their curriculum, we who believe in the power of pragmatic liberal education must develop broad, contextual learning that enables our graduates to pursue meaningful work and lifelong learning. Yes, ours is a merciless economy characterized by deep economic inequality, but that inequality must not be accepted as a given; the skills of citizenship and the powers of creativity enhanced through liberal learning can be used to push back against it.

At a time when many worry about the fate of the creative humanities at American universities, Hamilton reminds us, at many levels, that education can help enlarge the power of engaged citizens to overcome traditional hierarchies. Wesleyan University has created the “Hamilton Prize” to reflect our commitment to educating young people who, after all, have the potential to revitalize our economy, animate our citizenry and energize a culture characterized by connectivity and creativity.